Approx 2200km, 1 month. Spring 2016. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

The Silk Road used to carry camel train-loads of goods between China and the West. In the olden days, there was a mass of tracks and routes across two deserts to either ports on the Caspian Sea, or through what’s now Kazakhstan to Russia.

Having just ridden across India, I (probably sensibly) decided against crossing Pakistan and Afghanistan by myself, and flew into Tashkent from Amritsar in early spring 2016. Then I prepared to head west.

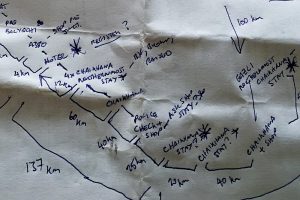

I’m usually an outline planner when I’m touring. Get a vague idea of where to head, and sort myself out as I go. Uzbekistan’s a bit different, though. There are hardly any roads, and very few decent-sized towns, so the route pretty much sorts itself. Tashkent to Samarkand, to Bukhara, across the desert to Khiva. Across more desert to Beyneu in Kazakhstan, turn left, and head for the seaside. The Kazakh section used to be known as ‘the worst road in the world’, but there’s new tarmac across most of it now. A bit over 2000km, pretty flat, should take about a month, giving time to explore the ancient Silk Road cities en route.

Easy!

There were a few complications though. There are only a handful of settlements in the last 1500km (900 miles), and it’s mostly through the desert, with water sources around 100km apart. Information on that whole section is pretty sketchy, as it’s not exactly on the tourist trail. And Uzbekistan is an ex-Soviet country with a dire economy, and very little infrastructure. So, there were three compulsory errands before I left Tashkent: a high-tech map of the desert section, a data SIM card, and illegally changing $200 into bricks of local currency. All ready to roll!

First, the relatively easy bit. All main roads (there isn’t much else), but substantially less busy than the UK or Europe, and much less terrifying than India. You do suddenly realise how big the gaps are between services, even in this relatively densely-populated part of the country. You also realise that stopping in villages for a smoke is a bad idea if you want to make progress – three invitations to Uzbek weddings, before I’d covered 50 miles on day 1!

After a few long but easy days, you get to Samarkand – famous Silk Road city number one. Samarkand is one of the Islamic cities that held on to science, astronomy and so on while Europe forgot how to build toilets for 500 years during the Dark Ages. So we owe them.

It’s still got some superb architecture, like the Registon, though quite a lot of it was reconstructed under the Soviets. And the rest of the city is really only interesting if you want to see a typical ex-Soviet town. Tower blocks, potholes, dodgy pizzas and lashings of vodka. Lovely…

Back on the road, the weather worsened a little. Going in spring meant that I’d avoided the 40-degree heat of summer, which would have been unbearable. But occasional headwinds and heavy showers, combined with tedious, flat, straight roads made for a less than happy bunny on occasions.

And yes, I’m still using those shades four years later!

It’s worth the dull sections though, as you continue west, and eventually get to Bukhara. It’s smaller than Samarkand, but I think it’s much prettier, and has the whole old centre rebuilt, including several ancient markets, and this rather stunning square.

Add a few camels, and it’s easy to imagine the bustle of traders meeting from east and west, as well as the amount of manure that must have been all over the narrow streets.

The road gets harder after Bukhara. Fairly civilised for the first 100km, then it’s just one long straight line for 1000km, all the way into Kazakhstan. That’s longer than Great Britain! There are just a couple of smallish towns in the middle, and a roadside shack or two (chaikhanas) each day or so for food and water. It would be fine if the wind stayed in the same place for a week and a bit, but what are the chances of that?

The first stretch of proper desert starts after Gazli, a little village north-west of Bukhara. I woke up early, slightly worried about hitting a chaikhana over 100km away for the night. There was nothing between me and it. But the lesson for the day was that, with a tailwind and a brand-new road to ride on, desert riding can be awesome!

I normally think that over 100km (60ish miles) is a fairly long day on a loaded bike, and 130km (80ish miles) is a sensible maximum. And I normally average about 20kph (12mph) when moving. My first day in the desert was astonishing. Very flat, and the wind just picked up the bags like sails and blew me along the road. Barely any effort, and I had lunch where I thought I’d be sleeping, and just kept on going. 133 miles in a day. Wow! I didn’t know then that the desert was just playing with me. Things were going to get a whole lot harder.

It started the next day, another long one to the beautiful town of Khiva, the last of my Silk Road cities. I’d had a nice night in a traditional chaikhana, chatting with the family, and experiencing an open-fronted long-drop loo overlooking Turkmenistan (that’s definitely a once-in-a-lifetime experience!). On the road, the rain came as a shock. Not so bad on the tarmac, but an ill-advised short-cut put me on gravel for a while, and things got messy quickly.

A lot of the ‘sand’ in this desert is actually the evaporated remains of the Aral Sea, which creates a mud that’s a nasty mixture of sand, dead sea creatures, salt, and various chemicals. It’s toxic and sets like concrete. And is a fairly strong response to anyone who claims that humans can’t permanently damage ecosystems – that’s a whole sea destroyed in a few decades. For cotton for cheap T-shirts.

It could have been the smell of the mud that upset them, but I also suffered my only organised dog attack of the whole tour that day, spending ten minutes dripping and shivering behind the bike before three locals in cars eventually managed to drive the feral canines away. I was on the road for over 12 hours before I finally rolled into Khiva as darkness fell.

Khiva is beautiful, which was something of a consolation after spending an hour knocking mud of the bike and panniers the next morning. The effort involved in getting there really makes you think how thankful those ancient travellers must have to see this oasis on the horizon.

Still, you can’t stay at an oasis for ever. The road goes on. Straight on, in this case. That thin line of deteriorating tarmac heading inexorably for the country next door. Just another 500km or so until you can change direction.

A day or two later, the wind bit back. After the 230km day earlier on, I knew that the elements were going to kick my arse at some point, just to even things out. I was just two long days from the border, at a truck stop in the middle of nowhere, with nothing but a notorious prison and a small village between me and Kazakhstan. Nearly there. But the border may as well have been on the moon that day.

I knew there was a headwind, so I started early. But what a headwind! I finally got out of sight of my start point after two hours, and had got 20km up the road by lunchtime. And I was exhausted. Ouch!

This felt like a catastrophe, but it’s often when things go wrong on a tour that other people all over the world get to show how nice they are. I sat by the side of the road for half an hour, and then got rescued by a truck full of road workers. There are not many times that sitting in the open back of a Soviet-era truck with twenty sweaty Uzbeks counts as a good result, but that day was definitely one of them! I spent the next few hours at the workers’ camp, and then they flagged down the only bus of the day to get me to Jasliq prison at near light speed. Alarming though it is to be skimming over potholes and sand at sixty miles an hour, while trying to chat with the clearly drunk driver, it was much better than trying to push another few kms against that wind.

And there’s always another day. There’s not much in Uzbekistan after Jasliq. The road is flat, and straight along a compass bearing. I took pictures in the morning, lunchtime and afternoon. The only thing that showed I was moving was the little blue dot on my phone.

In the whole day, I saw two interesting things: a wild camel, and the guts of an old music cassette, which took me right back to the 80s.

The desert border crossing was lovely. The locals push tourists up to the front of the queue, so I had time for a nice cup af tea and a chat with the Kazakh border guards. Then it was just another 70kms of very straight road (but on dirt this time) to Beyneu. I was in Kazakhstan, and I could change direction for the first time in a fortnight!

As you can see above, once you’ve turned towards the Caspian Sea, the view changes dramatically. The ‘worst road in the world’ was now newly paved, but there was still another 450km of desert before I got to Aktau on the coast. Still time for me to get blown off the road by a gust of wind, have tea with some camel herders, and get rescued again (this time by a passerby in a 4×4).

This was one of the hardest sections of my round-the-world ride. Not so much physically (there are headwinds everywhere, after all), but mentally. It’s intimidating to see that much empty space in front of you, and you’re very much on your own a lot of the time. But it also ends up being one of the most memorable sections.

Memorable partly because of the starkness of the countryside. Once you get used to it, there’s something oddly beautiful about it.

Partly because of the history and culture of those magnificent Silk Road cities, and appreciating some of the hardships that those early travellers must have had without phones, roads or bicycles. And partly because this section of the ride, like all the others, reminded me that if you’re in trouble, the vast majority of people anywhere in the world will try to help you out.

Lastly, it’s memorable because it ends. And that gives you perspective. You never welcome the sight of a crumbling Soviet port city as much if you haven’t struggled a little bit to get there. And the simple basics like a clean bed and a cold pint feel like massive wins after weeks in the desert.

The harder the road is, the more you can appreciate the smallest of comforts on the way. And maybe that’s something to remember at the moment.

Written by Tim Snaith, BBP volunteer & coordinator